For the overwhelming majority of our evolutionary history, we have lived in semi-nomadic tribes. As the human nervous system evolved over tens of thousands of years, we lived in small, highly-bonded groups of approximately forty to one hundred people.

For each child in the tribe, there were about sixteen adults available to provide them with care and attention. If you consider your own childhood, how many adults were available to you? For most of us, it was one or two. And at school we shared one adult with about thirty other children.

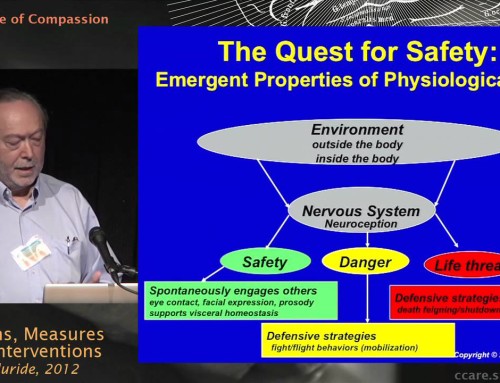

So while we have evolved to be very social beings, we rarely get our basic social needs met. This is especially critical in childhood, when our nervous system is still developing. The vagus nerve, a.k.a. the “compassion nerve,” is what controls our ability to engage with others and to give and receive love. In the last trimester of gestation and in the first 6 months of life, the vagus nerve grows a fatty sheath, a process called “myelination,” which allows the nerve to transmit signals very quickly. Stress, trauma, and neglect during this phase of life results in incomplete myelination and hence a less-than-optimally functioning social engagement system. This is one aspect of “attachment trauma,” which leaves a person even more vulnerable to the effects of “shock trauma.”

When we compare our long history of tribal living with our modern lives, it becomes clear why there is a pervasive sense of loneliness and insecurity in our society. We all have a deep need to belong. The more we heal our own trauma and improve the functioning of the vagus nerve, the more we are available for connection with others. And the more we extend ourselves to accept and include others, the more we can heal our collective pain of isolation and fragmentation.